Power, Gris-Gris, and the Plurality of a Haunting: Maryam de Capita's New World Order

Today, Kristina Kay Robinson visited the Taller. She did not come alone. Maryam de Capita of the Temple of Color and Sound, citizen of Capita, Republica, and devotee of the Blessed Mother traveled with her. Whispering sweet nothings, waving palm fronds and wearing gold earrings, Maryam laughed and swayed her way through and around the space. She tinkered with the moodboard. She left a perfumed handprint on rule #1 (how do you escape). She broke our good rum glasses and spilled honey on our altars. We don’t call these accidents. We call these blessings. Maryam came to let us know who’s the boss.

In this interview for Electric Marronage, Robinson sits down with Kin Curator Jessica Marie Johnson for a chat about her persona, Maryam de Capita and the New World Order Maryam offers her followers: A new order of human. A palimpsest for and of black freedom. Citizenship in marroon territory. Digital embodiment. And more. Read on….

EM: Tell us about yourself and Maryam de Capita. Who are you and what do you do?

Robinson: My name is Kristina Kay Robinson. I’m a writer and a performance artist born and raised in New Orleans. Who is Maryam and what does she do?

Maryam de Capita is a persona I embody at her will. Maryam lives in Capita, Republica, the capital city of a free Black republic on the Gulf coast of North America. Her last name comes from the Latin, “per capita” or “by the head.” In part, her family line includes refugees of the Haitian revolution accepted in the Louisiana colony, who were called “heads.” She is also a citizen of the Bambara and Natchez nations. Her last name also refers to those rebels who were captured and beheaded by the Americans during the uprisings, as well as to the practice of burying the heads of priests and holy men separately from their bodies to protect their knowledge.

Maryam is from a long line of devotees of the Blessed Mother. She’s worshipped in all her spiritual incarnations in the free territory, so Maryam is not the only “Maryam de Capita” in Republica, but maybe the most vocal for now.

Maryam is an artist, mystic, and entertainer. She’s the proprietor of Temple of Color and Sound, an itinerant gathering, ritual, and performance space. Maryam is sort of Republica’s official/unofficial ambassador. She’s been traveling about the world for the past few years. She is having fun, but misses home terribly.

EM: What made you meet/create her and how has she evolved over time?

Robinson: Maryam de Capita began as a persona in my poetry. An archetype of a kind or an energy that just started to narrate my work. I was thinking a lot about Miriam Iris Carey, LaVena Johnson, Latasha Harlins. These Black women and in Harlins’ case, a Black girl, whose deaths were just haunting me day and night. The lack of outrage, the way we just have to go on—Maryam’s voice came out on the page to talk back to that.

As I started becoming interested in alternative ways of story-telling, I found myself experimenting with the idea that she was a “persona” and not a function of my poetic voice. I was working a lot with my altar installations and sound as a way to supersede language and the need for us to “understand” each other to communicate. I was also thinking a lot about those methods that are non-verbal and the role those play in organizing rebellion. I was also dealing with a profound experience of personal silence due to intimate partner violence. I had an experience and it felt like someone just shut the light out on Kristina. Maryam took over my body, she started to speak for herself and go about the business of performing and saving my life.

Maryam’s temporality is very flexible. She is a time traveler. She and the people from her line are able to traverse space and time. They have developed a secret knowledge about electricity and density that allows them to move about as they need to across moments in history. Maryam instructs people who come to the Temple on how to access (to an extent) this mechanism of time travel, in the spirit of personal and collective healing.

“Maryam took over my body, she started to speak for herself and go about the business of performing and saving my life. ”

“Republica is a maroon society...but don’t over step.”

EM: What does Republica sound, look, smell, taste and feel like?

Robinson: Republica smells like rain, oud, bakhoor, trinity seasoning, frankincense, coffee, and fresh bread baking. It is hot and wet. People live on land and water. It is advanced architecturally, though what constitutes the basis of “advanced” might be different than in the rest of the continent. Their system for building on land and water prioritizes the environment’s integrity. Palms, oaks, magnolias, roses, pelicans, herons, crows, oysters and oyster shells are plenty. Lots of blacks, purples, reds in their varying shades are dominating colors The sound is cacophonous. There is always a lot happening in public space. Socializing, learning, working and celebration is kind of a continuum.

Sound is an organizing principle and strategy for gaining and maintaining freedom, so there is a lot of music. All genres of music are popular in Republica with special emphasis on Black American music like bounce, jazz, house, soul, screw, disco, freestyle, trap etc. It all gets mixed up into something called Preto/Petro in Republica. Preto means Black in Portuguese (a nod to the quilombos in Brazil) and petro is a reference to the fiery side of Vodou.

EM: Republica, the Temple of Color and Sound, and Maryam de Capita herself embody so much of what Dr. Yomaira C. Figueroa describes as a “reparation of the imagination.” What lessons about black freedom are we meant to learn from visiting Republica or meeting Maryam de Capita? Say something about how marronage operates in your work?

Robinson: Republica’s history of rebellion dates back as early as 1729, the year of the first Natchez Bambara conspiracy to overthrow the French colonial government. This took place about a decade after New Orleans’ establishment. The lesson about Black freedom is the people: We always fought for it. Freedom is our natural state; it’s natural for the body to do what it has to in order to find it. In our case, it was to rebel. By living in rebellion we are also bound to those in captivity. Temple of Color and Sound is a space where we affirm these truths through ritual, recreation, through song, dance and conversation. So it’s not about marronage as an exceptional state, even if it is exceptional in the experience of Black people. It’s about willing freedom to be possible for us and others. It’s a struggle where victory is the destination, but we travel and struggle regardless.

EM: You are something of an innovator of what Dr. Jessica Marie Johnson has described as black digital practice. Could you talk a little bit about how you use digital and social media to create the world Maryam de Capita inhabites? Do you have any favorite tools that you use to create that you could share? Explain your technique and why you chose it for this worldbuilding?

Robinson: As an individual I was becoming frustrated with the effect that social media was having on my mood. Post-trauma it felt pretty hellish to try to engage it. I thought about ways to use it that felt better; that didn’t feel like it was reinforcing the ways I felt suffering sexual violence had socially isolated me. I thought of Instagram with its capacity for still and moving images as a storyboard into another space, a new kind of “form” where I could tell a story, go to a party, perform all the things that felt unsafe to do in physical space. I could stage for myself things that maybe the art world wasn’t ready to let me do in the space of an institution, as a performance artist. It was also a response to the climate of surveillance. I felt very acutely the connection between state surveillance and gender based violence and I wanted to push on that. Like if you’re going to “follow” me, it won’t be a straight line to get to me.

I saw a show a long time ago where a woman used a scarf to embody multiple characters. That inspired me a lot. So my favorite thing to use is myself. Stand in front the screen and see what I can evoke with the use of my body.

EM: Your work is deeply rooted in New Orleans and New Orleans history. Why is New Orleans so important to you? What is it about New Orleans that fuels your art? What does your New Orleans look, sound, and feel like?

Robinson: Republica in some ways is an homage to the New Orleans I knew pre-Katrina. As more and more people arrived to the city, Black and white, in the storm’s aftermath, and as I began to travel more, it really struck me how much of a nation within a nation we had been. Distinct language, ethics, codes of behavior, traditions, even law. We grew up very differently than what the majority culture is in the country, even what we may think of as the hallmarks of Black American culture. We have a distinct experience within and outside of that. The video of Soulja Slim’s secondline after his funeral—that is New Orleans to me. I miss it.

EM: Before you go, Taller Electric Marronage is guided by the four rules (how do you escape? how do you steal? what does it feel like? and *whatever) of marronage. If you had to choose one rule (or have Maryam choose a rule) to follow, which would it be and what would you do?

Robinson: The escape route is oftentimes located in the natural pathways of the body. Steal whatever of theirs that is not nailed down—and that too if you have the tools. Marronage feels like electricity, like illumination—you expand, you gather force, your presence is undeniable but you can’t be touched.

There is a saying in Republica: “A fugitive is not free, but a fugitive is not a slave. Mastering what to share and what never to reveal, this is the life of the fugitive—the one who remains free by their wits.”

EM: Are there ghosts in Republica?

Robinson: Definitely. There are also those entities in between the living and the dead. So much transpired on the road to freedom, so there is a lot of activity in the ether of Republica. Part of Maryam’s most challenging work in the Temple is teaching herself and others how to manage, submit to and/or resist their presence. A lot of discernment is required.

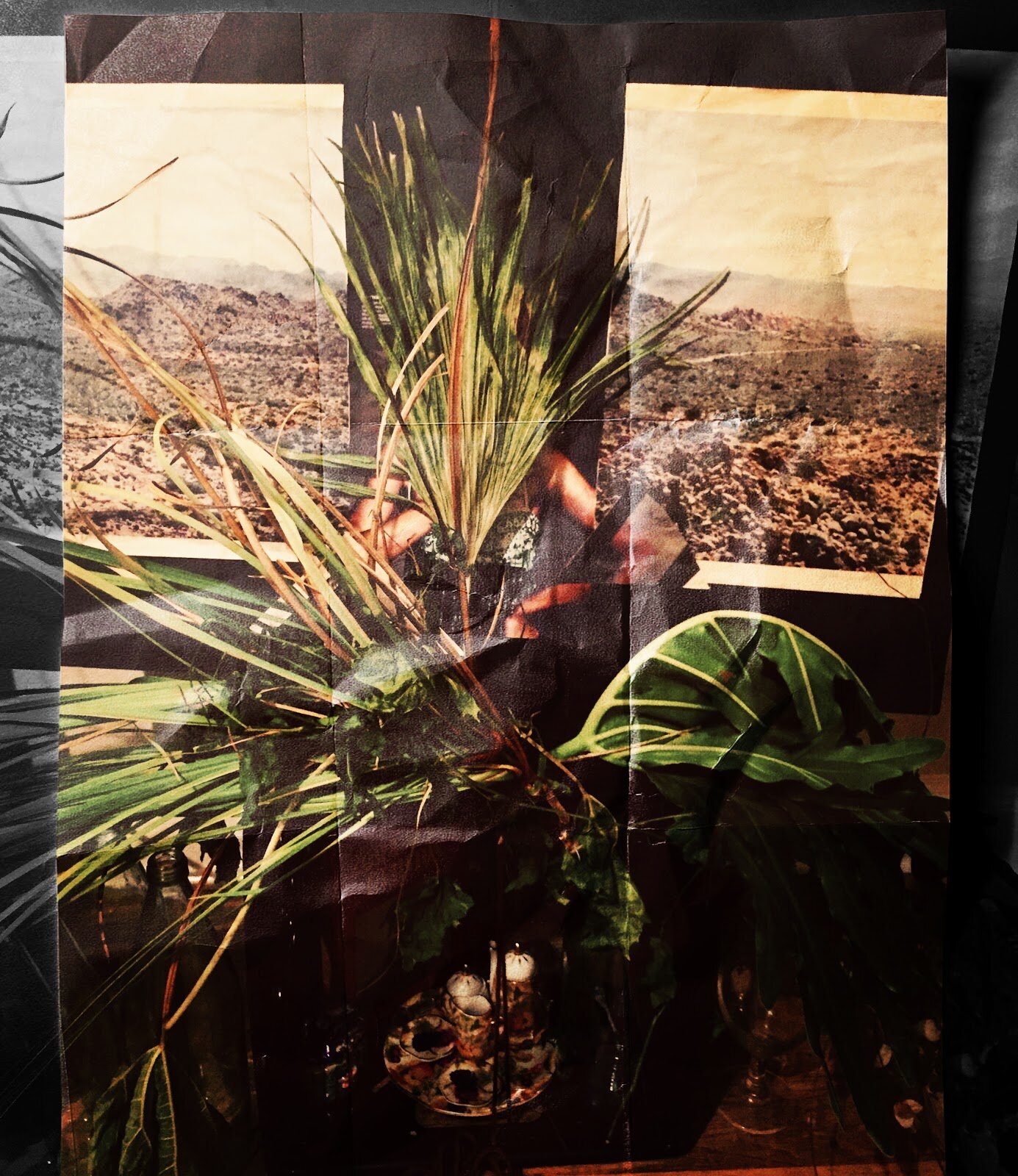

Image: CAMARADERIE, 2021 (Credit: Kristina Kay Robinson)

EM: Are there ghosts in Republica?

Robinson: Definitely. There are also those entities in between the living and the dead. So much transpired on the road to freedom, so there is a lot of activity in the ether of Republica. Part of Maryam’s most challenging work in the Temple is teaching herself and others how to manage, submit to and/or resist their presence. A lot of discernment is required.