A Radical-Love Politic: What Visiting Puerto Rico Taught Me About Kinship

“The shoal is a small uncovered spot of sand, coral, or rock where one must quickly gather, lose oneself, or proceed in a manner and fashion not yet known” –Tiffany Lethabo King.

When Professor Yomaira Figueroa encouraged me to attend the Proyecto Palabras PR (#PPPR) and Yagrumo Study Away program in Puerto Rico, I was both excited and reluctant: my Spanish-speaking skills were limited; and the other most obvious explanation for my reluctance was that I was Black with no Puerto-Rican ancestry. What would I be doing there? Would this make me voyeuristic? How do I attend this trip ethically and responsibly? My fear of reproducing colonial ways of relating (i.e. expropriating/appropriating culture) fed into my hesitance. I feared I wouldn’t know how to relate, how to belong, how to exist in this space not yet known to me.

Upon arriving at the San Juan airport, I found myself on a conceptual shoal where I was indeed trying to gather this lost sense of self as I was thrusted toward the unknown: would I be able to communicate with others? Would my presence there be questioned? My Black/Americanness felt hypervisible.

Betty Santiago, the program coordinator, warmly greeted us in Spanish; I smiled and listened attentively—though I only caught a few words. Finally, she asked: does everyone here speak Spanish fluently? While others proudly admitted they did, a few of us admitted we did not. Without judgment, she spoke English—despite it not being her first-tongue, to better welcome us. I arrived in San Juan, Puerto Rico over a year ago today, and I still think about Betty—my gratitude still overwhelming for the ways she made space for us.

What does Kinship Sound Like? A blended and vibrant soundscape

What I remember distinctly about Adjuntas is its sound. Each morning around 4 am, I was awoken by roosters clucking. Around 6 am, the blasting music would start. And, all throughout the day, people could be heard speaking, laughing, joking, and working. Animals were given free-range as unleashed pups and uncaged roosters walked the city as freely as any human. The vibrant mesh of sound and movement seemed to create this sense that all was one and what seemed (from a U.S. perspective) like a discord of sounds was actually harmony in motion. The people respected the roosters’ need to crow, the loud music in the morning was the community’s alarm clock, and the unleashed dogs were essential members of the community formation. Life in Adjuntas represented a shared and blended ecosystem: front doors were kept open as sunlight penetrated homes and trails of ants made their way indoors for snacks.

In Adjuntas, kinship sounded like harmonious distinction because kinship meant making space for various, distinct life-forms to exist as one, at once.

“Puerto Rico was a woman’s country. […] We have always been here doing what had to be done, working, eating, sleeping, suffering, dying…” – Aurora Levins Morales

What Does Kinship Feel Like?

Betty was everyone’s mother and everyone’s friend. She gave us medicinal plants to sniff while making our way up the mountains; for motion sickness, she said. “I always have these for my daughter.” She cared especially for the island, and during our time there, she did for us as she would for her own daughter. This is what it means to be kin.

On this trip, I experienced the dynamism of kinship: it was sudden in its formation, explosive in its impact, and warm in its connection; ultimately, it has no criteria that could contain it: it was not on the basis of blood or a shared spoken language. It was on the basis of care and compassion.

So, when Betty offered me the very shoes off her feet because my feet ached on our hike up the mountain, I knew that she did not see me through a lens of distinction but through one that made connection our mode of relation. Connection became the mode of relation in many other ways as this trip connected me to Demarius, a fellow holder of the Similton ancestry. Our last name is extremely uncommon; so, sharing it was enough to know we were connected. In this place so seemingly separate from our birthland, we still found kin+connection. Cousins, we called each other—though we never confirmed concretely our relation. Still, I don’t feel the need to confirm it because kinship is dynamic and more importantly, it is decisive: we asserted our relation, and our assertion is all that it needs to exist.

“kinship is dynamic and more importantly, it is decisive: we asserted our relation, and our assertion is all that it needs to exist.”

What does Kinship Look Like?

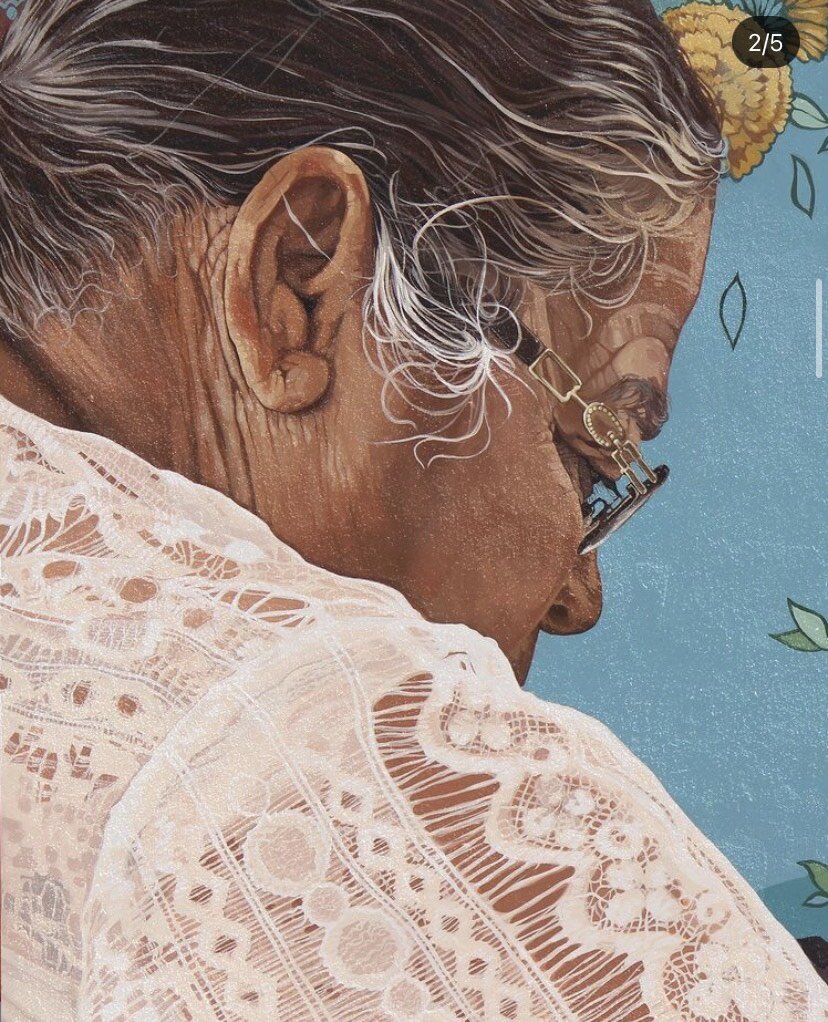

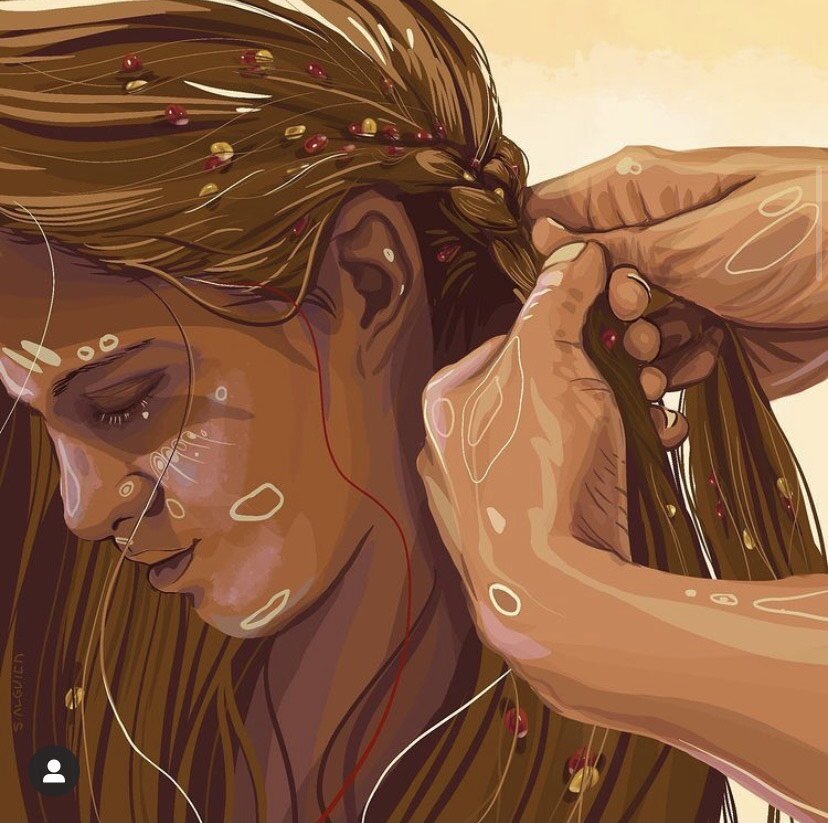

As I ruminate on kinship, I think also of Colectivo Ilé and Colectivo Moriviví: two organizations that insist upon connection—rather than distinction—as the preferred mode of relation. Colectivo Ilé (IG: @colectivoile) has a mission of challenging Eurocentric beauty standards on the island and encouraging Puerto Ricans to assert their connection to Africa(ns) by marking Afro-descendiente on the census and by teaching them how to wrap their heads in traditional African cloth (#turbanteoconsciente).

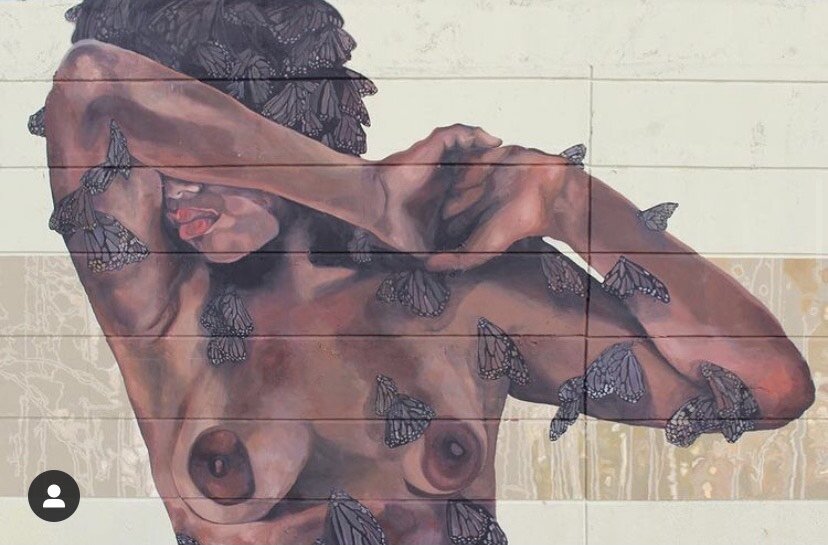

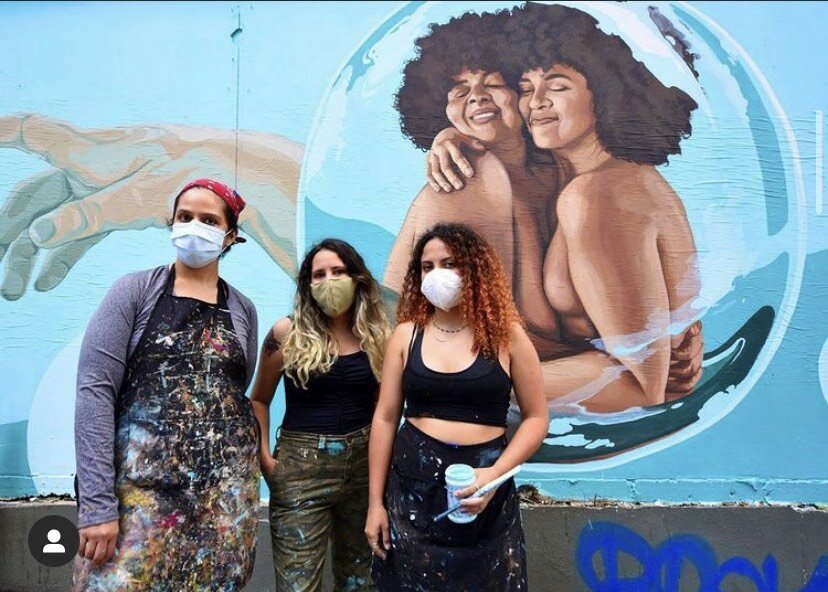

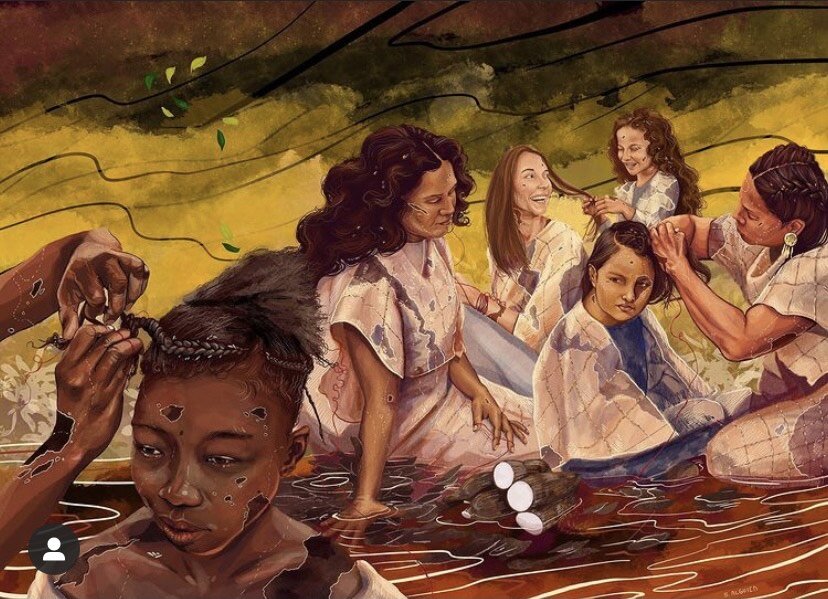

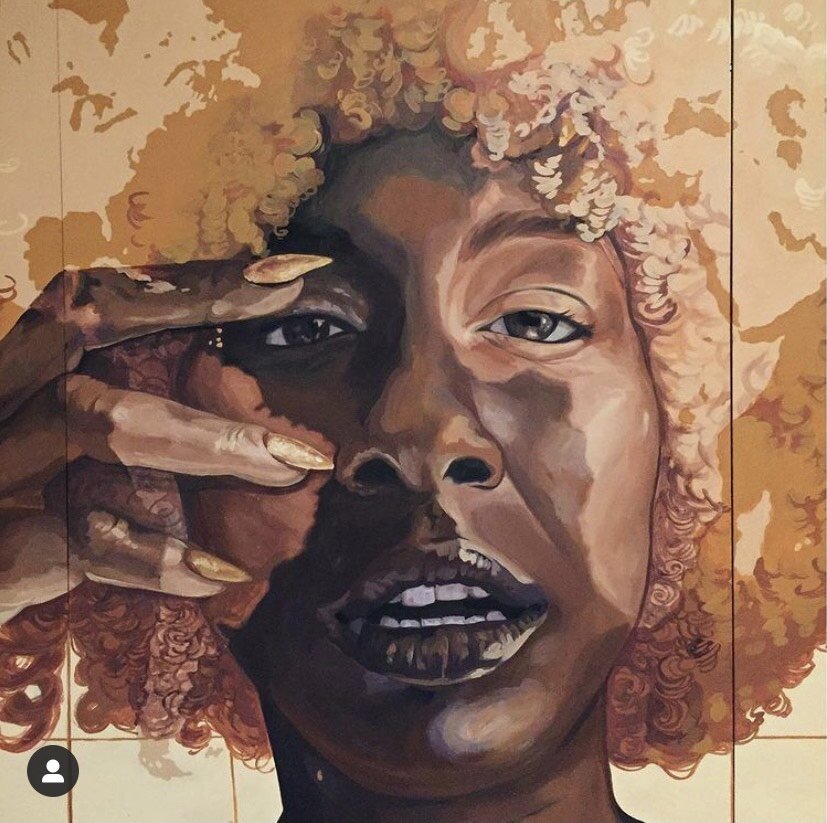

Colectivo Moriviví (IG: @colectivo_morivivi) is a group of feminist muralists who insisted upon representing the Black Dominican community in one of their most famous murals. “We have a clear Dominican Community that we had to represent Black bodies.” Chachi’s statement shows a decisive commitment to connect and assert kinship across cultures/communities—and it is this assertion of kinship that makes the island such a powerful space of intimate possibility. The following photos are from their Intstagram:

Through deciding to make connection, care, and compassion their mode of relation, these Puerto Ricans carried me from the shoal (this place of uncertainty and losing oneself) to the shore: a place where we all communed together. And, for my short time that I was there, Betty and so many others made it possible for me to feel like a valuable part of the complex, vibrant, and dynamic kinship formations that constitute Puerto Rican life and enables a radical-love politic that defies colonial ways of relating, being, and thinking.

To get a glimpse into Proyecto Palabras PR in motion, enjoy the following documentary shot by MSU student Shane Heath.

—Jaye Similton