Tell Me, What Does Freedom Feel Like?

Rule 3: Movement

Freedom is not a place; it is a state of being[1]

Mas!

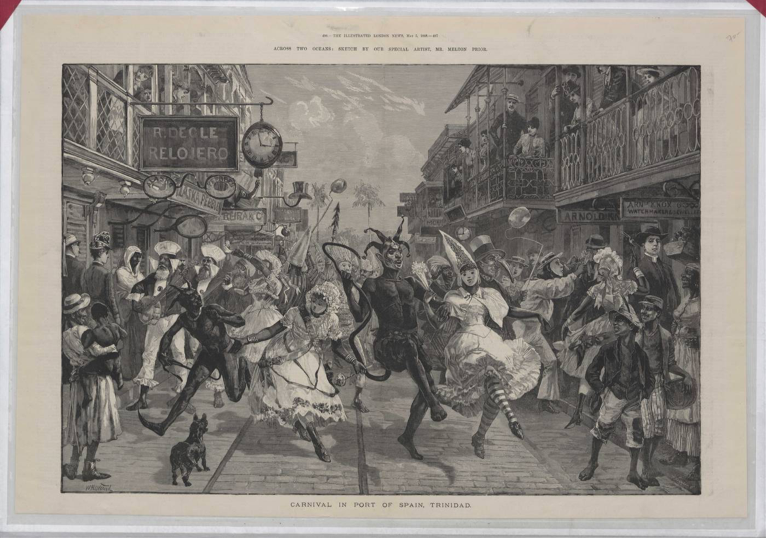

Masking is a carnival ritual that allows masqueraders to “talk-back” to the state order by adopting alternative identities, behaviours and gender expressions as a tool of resistance and expression of freedom.

“Keep everybody off the street, these animals off the streets, they are running around Miami-Dade County acting like they have escaped from a zoo. Lock them up at 5 p.m so the streets can be nice and cleaN.”

tRINA, bLACK CAPITALIST AND rAPPER, 99 jAMS rADIO 2020

“When the west wing of the police building was inaugurated, swarms of lewd women and street raggamuffins, were gesticulating, dancing and voiceferating like so many monkeys in an African forest.”

tIMES, bRIDGETOWN, bARBADOS, mARCH 27, 1872

Mas is a celebration of the subordinate. The mask is a tool of the underclass. It offers possibilities for false identity making, new identity making, and revelations of the self. The masquerader obstructs state and public surveillance by inviting themselves to be seen. Masquerading as a self-adornment practice allows those who were barred from the promises of freedom; upward mobility, ownership over body, sexuality and labor, and the opportunity to chart their own meanings of freedom. Participating in mas celebrations offers black women and men the possibility to reclaim ownership of the body and the self. Through the public performance of open rebellion, masqueraders demarcate unsanctioned space where social mores of proper gendered and racial behaviours become inadmissible.[2]

Instructions from our band leaders[3] :

“Its mas everywhere, its pure bacchanal in di streets. Masqueraders, jump up, wine up and mash up di place!”

Translation: Everything Must Go.

“If you is not a masquerader, please get off di stage, dis is di time for di true masqueraders”

Translation: If you are here to dance with your oppressors, please leave the protest, we are here for revolution not reform.

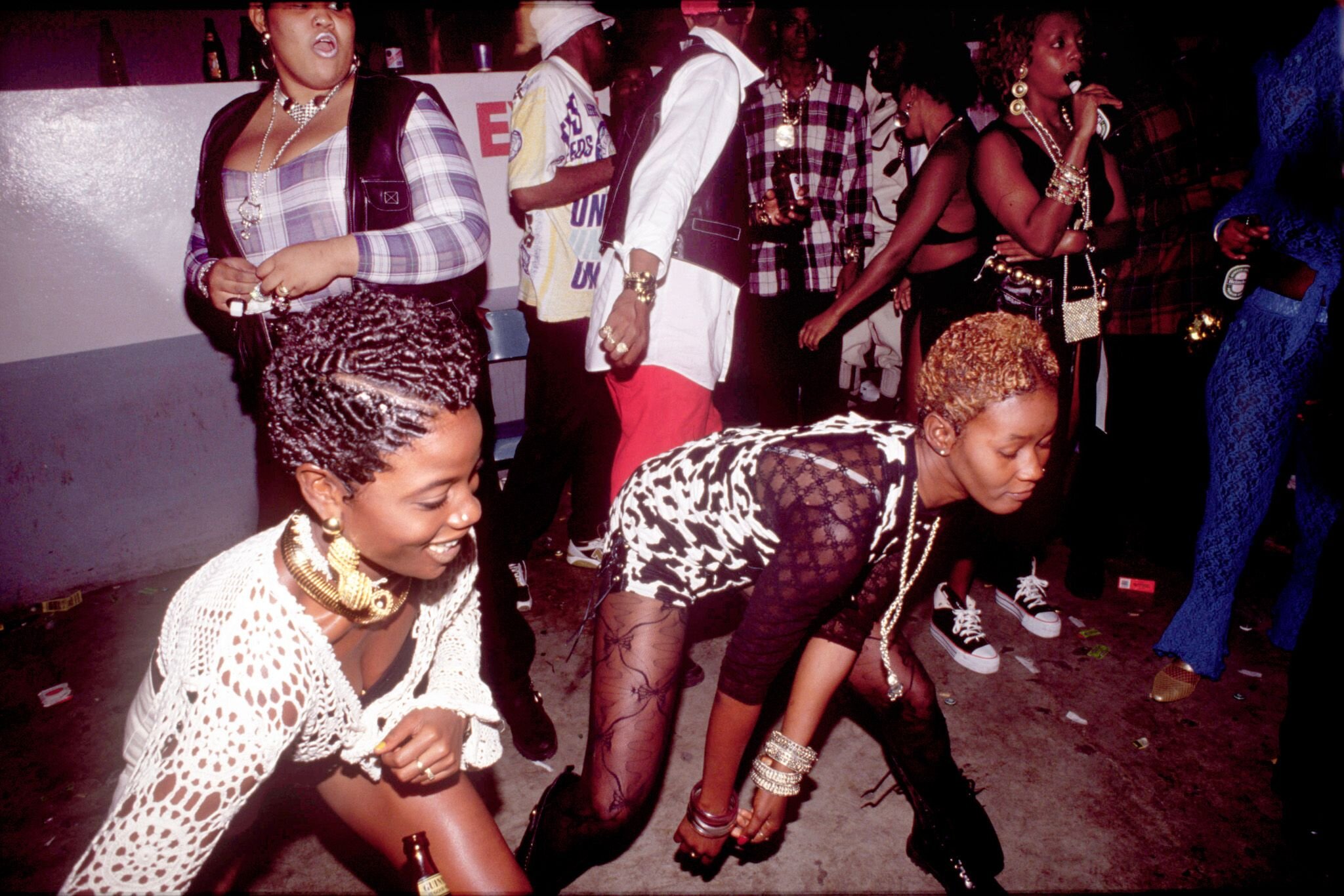

“Out and Bad”

“Out and bad” is a praxis of the Jamaican underclass that mocks notions of respectability. Rejecting social mores of “civilized” behaviour, badness is rooted displays of threatening and unabashed masculinity. To be “out and bad” is to participate in a public performance of revolt through acts of disruptions, glamour and confidence. [4]

The curfew is a modern vagrancy law.

Getting on bad, scores of dissolute men and women swarm the streets in a loud defiance of state order.[5] “We ain’t afraid of no curfew!”[6] becomes an anthem that reverberates across the underclass. Unquelled by attempts to confine their freedom of movement, they flaunt their badness and exhibit their rebellion in all of its beauty and glamour for those who wish to bear witness. Lining the streets, fully adorned, black movement becomes a grammar of freedom.[7]

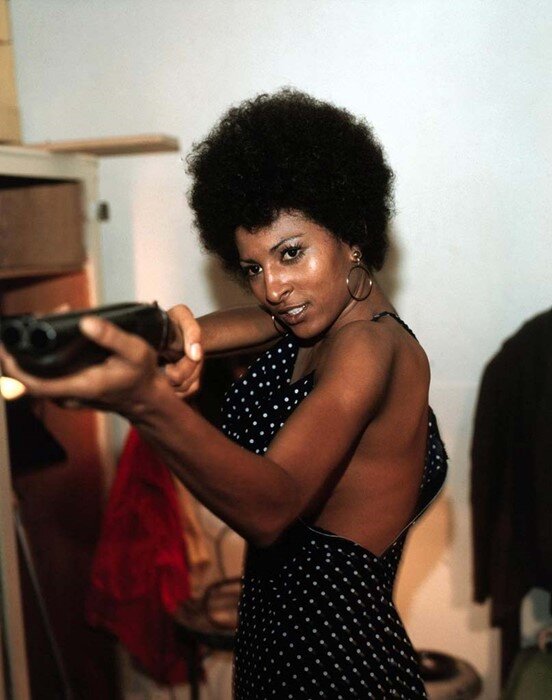

Erotic

“the erotic” is the embodiment of what it means to feel in all of the self’s capacities.

the erotic is often misnamed by men and used against women[8]

the erotic is often misnamed by us.

The Caribbean offers and embodied archive and a theoretics of Black freedom expressed through movement. Across the Atlantic, our bodies have enjoined in choreographed rebellion through ritual performances of masquerading, bad behaviour, and a celebration of our full erotic selves. We reject a social order that demands our resistance be neatly packaged to fit within the parameters of an anti-black capitalist state structure dependent on continuous cycles Black labour and Black death. Instead, we parade our visions of freedom through the streets, and demand that our presence is not only seen, but felt.

Outro: A Play by M.NourbeSe Philips:

“Lock we up, lock we up! We waiting, come and lock we up!”

As the women chanting these words, they moving up the street

again toward the men. Boadicea tearing off her dress and now she

standing naked like the day she born in front of her troops and the

police officers. The women shouting out their approval and everybody

tearing off their dresses. Some of the men turning away, their faces

disgusted and angry at all that nakedness in front of them. The men

pulling back even further. Over her head, Boadicea waving what was

once her dress, but is now a flag.

Now Boadicea turning her back on the police and talking to the

women:

“Is fraid we fraid dese men?”

“No!” the women roaring back at her.

“Who dese men protecting?”

“Not we, not one o we!”

“Who de street belong to, dem or we?”

“The streets is we own!”

Boadicea turning now to face the men: “You see we here in all

we nakedness—you see any of we shame of it? Not one, not one a

we shame of we nakedness or frighten of you.”

Halle-Mackenzie Ashby

[1] Neil Roberts, Freedom As Marronage. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015. 9

[2] Phillip, Kimalee. “Gender Bend and Play a Mas’! Confronting the Gender Binary.” (2014) Caribbean Review of Gender Studies. Issue 8.

[3] A band leader is the lead director of masqueraders during carnival, they are responsible for hyping out the crowd and encouraging public performance. As well as, keeping street walker/voyeurs off the “stage.”

[4] Nadia Ellis, “Out and Bad: Toward a Queer Performance Hermeneutic in Jamaican Dancehall,” Small Axe 1 (July, 2011), 8,9

[5] “Getting on bad” is a saying the English speaking West Indies that exhibits a parallel meaning/connotation of “out and bad”

[6] Video of men taking to the streets in Baltimore to show their refusal to be confined to Maryland’s state sanctioned curfew: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Np_vgyfzAIg

[7]Annette Joseph Gabriel, “Mobility and the Enunciation of Freedom in Urban St. Domingue,” Eighteenth Century Studies, Volume 50, 2, (2017). 216

[8] Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power.” In Sister Outsider, 53-59. Boston: The Crossing Press. 56

Images in order of appearance

Image 1. “Resurrection at Sorrow Hill,” Jason Audain

Image 2. @sbthecreator, “Winston-Salem circa 2020 pt. 2”

Image 3. “Palmdale Protests,” Jonathan Paz

Image 4. Melton, Prior, Carnival in Port of Spain, Trinidad, 1888, Schomburg Center for Research in black Culture, The New York Public Library

Image 5. Ska Dance Hall, Photographer Unknown

Image 6. Shareef Grady, Ben Henderson

Image 7. “Dancehall Girllds, Kingston Jamaica, Cargill Avenue, Circa 1993,” Wayne Tippets

Image 8. Jonathan Ernst, Reuters

Image 9. “Photos from Saturday’s George Floyd Protest in Baltimore,” Lary Cohen, Baltimore Beat

Image 10. Audre Lorde, Robert Alexander, 1983

Image 11. Allison Hinds, Roll it Gal Music Video

Image 12. Pam Grier, Coffy, 1973

Image 13. “Homeless Black Trans women fund,” Jesse Pratt Lopez. https://www.gofundme.com/f/homeless-black-trans-women-fund