#QUEERNIGERIANLIVESMATTER: Gender, Sexuality and State Surveillance

Iyesogie Ogieriakhi, @sogiesnuggle

Starting last week, Nigeria’s #ENDSARS protests erupted across social media when the youth’s local demand to end police brutality found itself enmeshed within a larger global discourse to bring an end to state-sanctioned anti-black violence. For context, the Special Anti-robbery Squad (SARS) , which came into fruition in 1992, was recorded as being established in response to a spike in the number of armed robberies in Nigeria. Since its inception, however, citizens have repeatedly reported, through formal and informal networks of SARS, inherent corruption and abuse of power, namely: extortion, brutal and excessive force, gender violence, and rape. Most recently, discussions have surrounded how the state has expanded SARS’ reach by erecting the controversial Police Act. The Act grants police the authority to stop and search a person and go through their digital property (phone, laptop, etc). Lawyer Alfred Njokama lauds that officers can only search in cases where there “is reasonable suspicion.”

This law comes in the wake of SARS’ new focus on “internet crime”. More particularly, an effort to target Nigeria’s most notorious internet scammers, who have colloquially been called the “yahoo boys.” The name comes as a result of launching various 419 scams in Lagos’ popular internet café’s in the early-mid 2000s.[1] As a result of this aim, it appears that the Nigerian youth are disproportionately targets of SARS extrajudicial force.

What then, is reasonable suspicion? What becomes the factors and necessary qualifications of an internet scammer? More pointedly, how are internet crimes being fought by seemingly “random” street stop and searches?

Speaking with Channel 5 News, Micheal Sonariwo, who shared that he had been stopped five times by SARS officers “because they generalize I’m a yahoo boy, they generalize I’m a thug…because of the way I’m dressed.” Many young Nigerian men have shared similar testimonies, with accusations of police stopping them for having dreads, piercings, and tattoos.

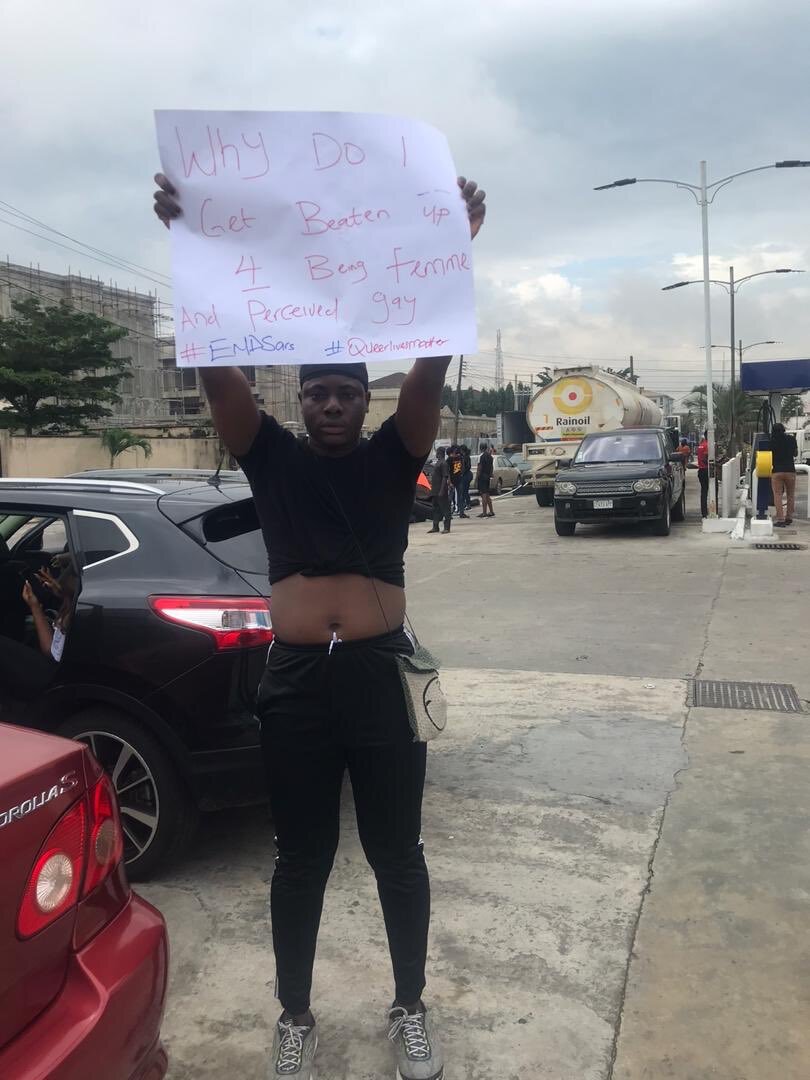

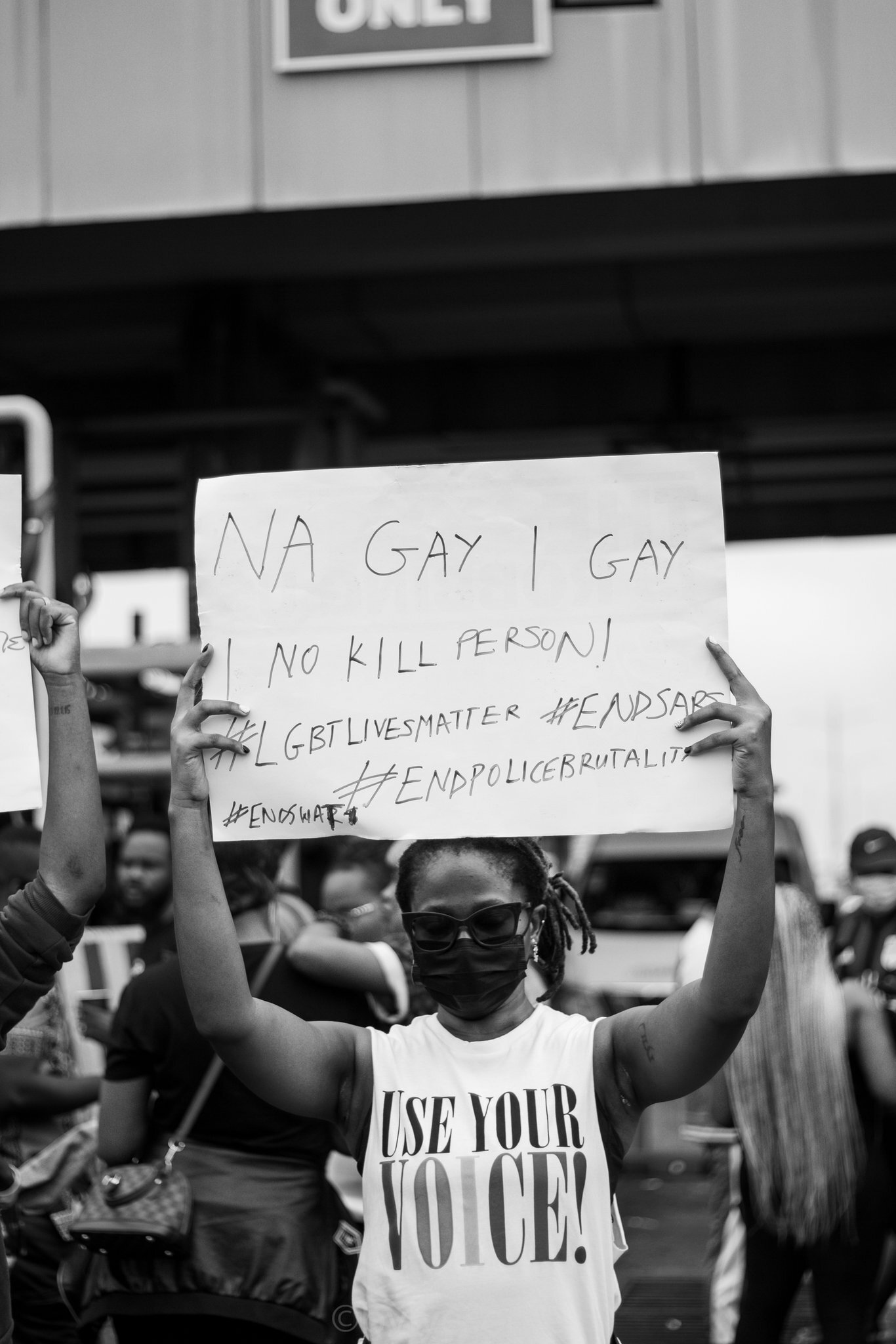

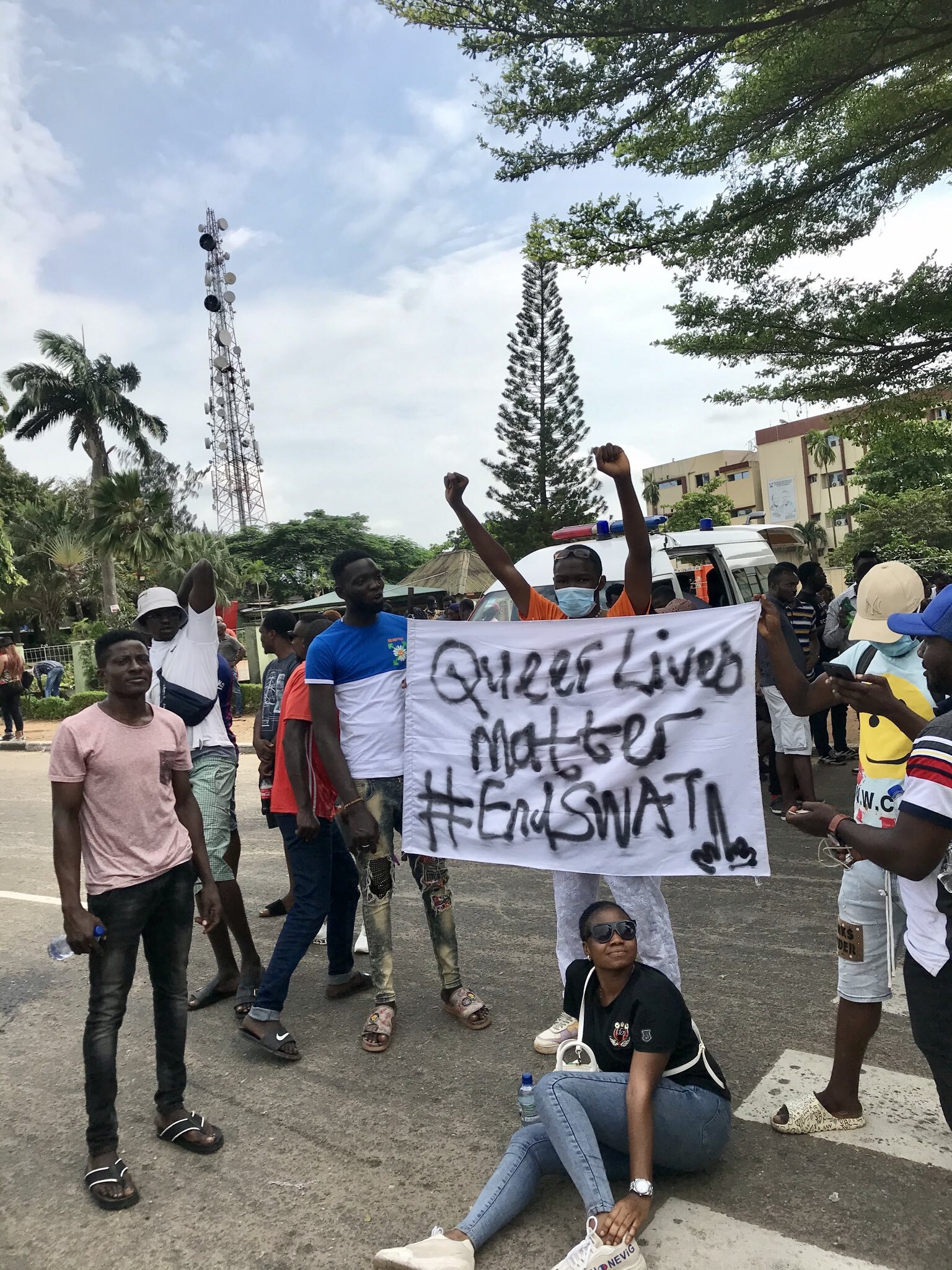

However, Nigeria’s queer youth have also cited particular types of gender and sexual violence. The stop and search ordinance has further served state efforts to criminalize, punish, and outlaw genders and sexualities that aren’t cis-heteronormative. It can be argued that, the state has been able to leverage SARS to attempt to regularly enforce the 2013 Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act. Officers have used the Police Act to target and identify queer youth by stopping people they believe to be gay because their clothing and appearance transgress gender norms. And citing that as “reasonable suspicion” to search through their phones and find private messages and pictures in an effort to condemn forms of free love.

People literally get arrested for looking gay. Queer brutality is a part of police oppression. They all intersect, and if we're pursuing a just society, you CANNOT harass or dehumanize people for their biological rights to love. @TheyCallMePrada

Because the police on the road don't target people for being Hausa, Igbo or Yoruba. But they target us for being queer. I've never been harassed by police for being Igbo but I've been harassed for being gay. #QueerNigerianLivesMatter #EndSWAT #EndSARS #EndPoliceBrutalityinNigeria @Kayode_ani

What all these testimonies make clear, however, is how conceptions about appropriate gender and sexual behavior are central to policing and state governance at large. Who is a “yahoo boy” is intentionally left undefined. The yahoo boy, through legal and judicial opacity, who is at once male, becomes appropriated and suspended into this genderless category, where anyone can be a yahoo boy – effectively extending that state’s ability to police and punish marginalized genders and sexualities. People are punished for their potential for criminality, their gendered bodies, namely their choices of gender expression, become criminalized and scrutinized for perceivably deviant behavior.

Being publicly visible renders the Nigerian youth vulnerable to varied degrees of gendered and sexualized violence. What becomes clear then, is that SARS, and Nigerian policing at large, and protests against it, should exist within Pan-African genealogy of anti-police protests – but must be equally located within a British colonial legacy of using vagrancy laws and legal opacity as a tool to police gender, sex, and sexuality. Historian of gender, political thought and decolonization, Dr. Annette Joseph-Gabriel presented to my class this week, where she illuminated the process by which the colonies become better colonizers than the metropole.[2] What Joseph-Gabriel was making legible was how the traditions of the metropole, in this case, England, became so ingrained in the psyche of the post-colonial state that by consequence, they perfect and perform colonial governance in a way that is not only reminiscent but can, in some ways, arguably become equally if not more violent than the colonial state itself. Post-colonial nations have continuously attempted to establish their legitimacy by branding the state as heterosexual, to make claims to productivity and civility – the heterosexualization of the state requires the marginalization of gender and sexual minorities.[3]

A video of a protestor yelling somewhat rhetorically into the camera: “is it a crime to be Nigerian!?” I answer, colonial logics render freedom in all of its forms and expressions as an act of criminality that necessitates state-sanctioned violence.

Halle-Mackenzie Ashby

Other Resources on the Nigerian LGBTQI+ Community: https://therustintimes.com

To make donations to support protestors: https://feministcoalition2020.com

#QueerNigerianLivesMatter #ENDSARS

[1] Cole, Teju. Every Day Is for the Thief: Fiction. First Edition. New York: Random House, 2014.

[2] Annette Joseph Gabriel, . Personal Communication, October, 14th, 2020. For further reading, Joseph-Gabriel, Annette K., Reimagining Liberation: How Black Women Transformed Citizenship In the French Empire. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020.

[3] Alexander, M. Jacqui. Pedagogies of Crossing : Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred. Perverse Modernities. Durham N.C.: Duke University Press, 2005.

Image credits in order of appearance

@Blaise_21

Iyesogie Ogieriakhi, @sogiesnuggle

@TheKingWoman

@OKTimeliyin