AFRO-LATINX LAB

AN AUDIO/VISUAL/DIGITAL LABORATORY FEATURING AFRO-LATINX SCHOLARS DISCUSSING RACE, GENDER, SEXUALITY, QUEER IDENTITY, PERFORMANCE, POLITICS, AND MORE…

Alive in their garden

This group show features works by four Black Latinx diasporic artists — Joiri Minaya, Felli Maynard, Star Feliz, and Nitzayra Leonor — engaging plant materiality and aesthetics as portals of gender subversion, ecological justice, ancestral knowing, and healing. Visit the show here.

SPRING 2022 AFRO-LATINX LAB EXHIBIT & LECTURES

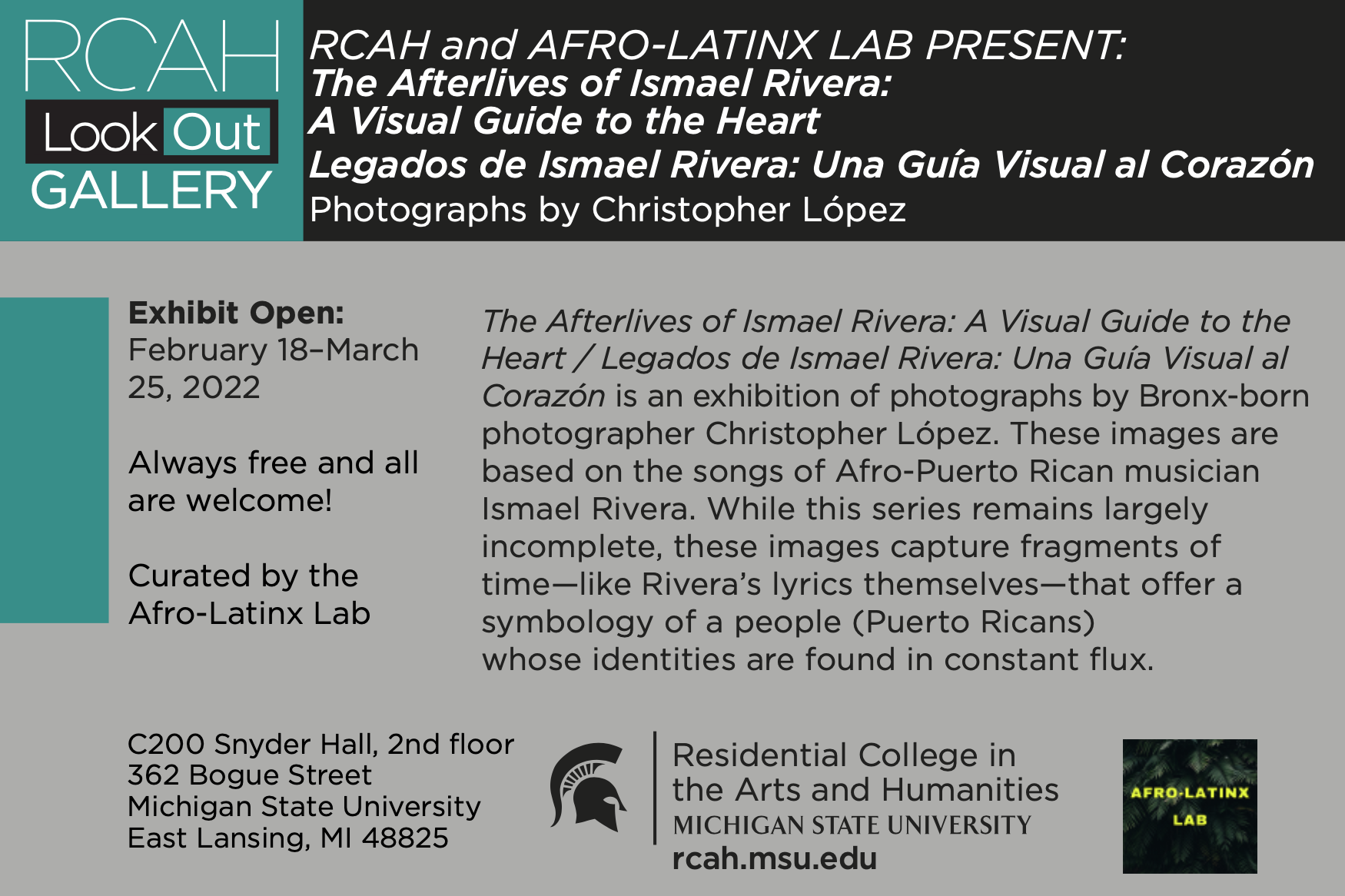

AFRO-LATINX LAB PHOTOGRAPHY EXHIBIT

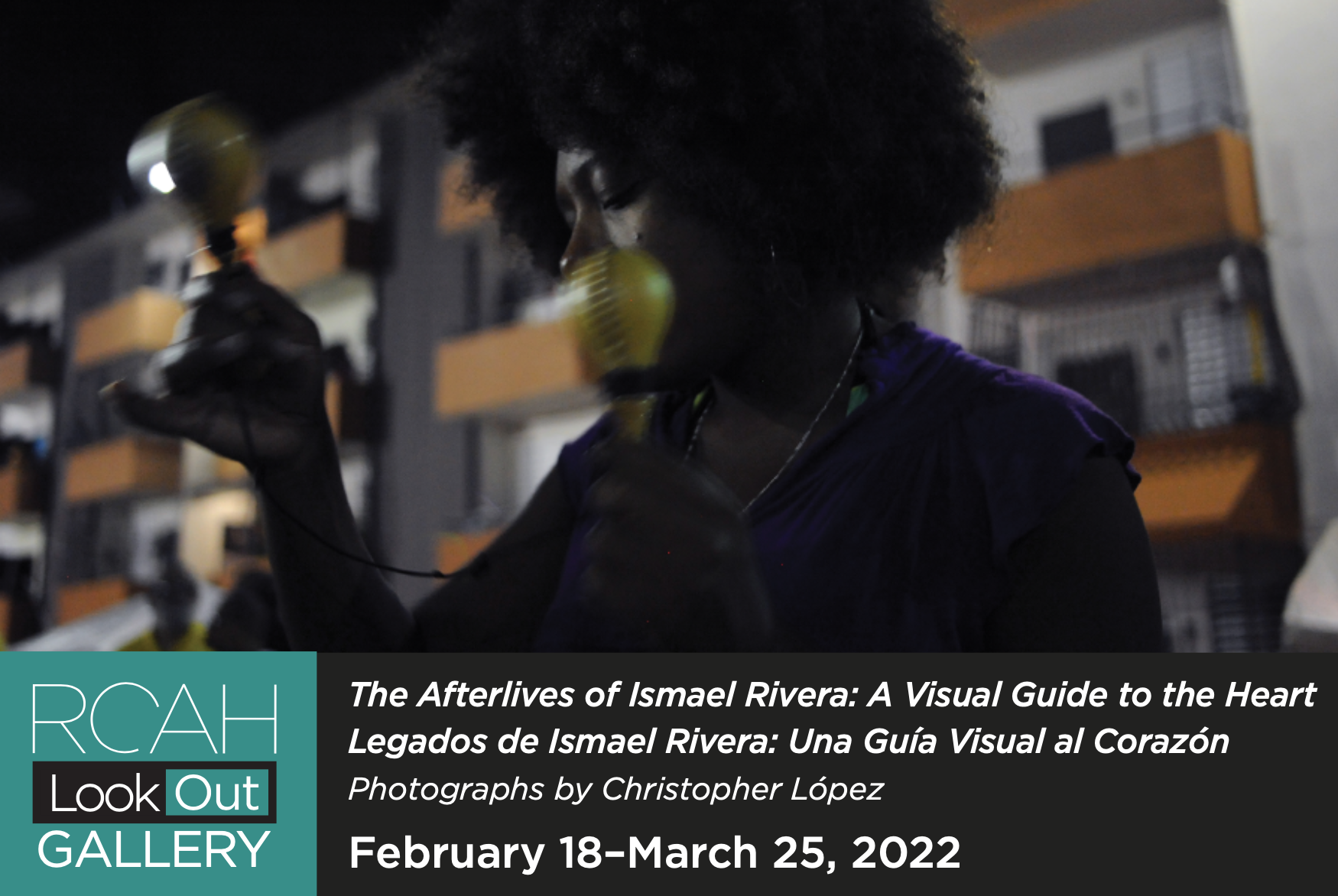

The Afterlives of Ismael Rivera: A Visual Guide to the Heart / Legados de Ismael Rivera: Una Guía Visual al Corazón

The Afterlives of Ismael Rivera: A Visual Guide to the Heart is an exhibition of photographs by Bronx-born photographer Christopher López curated by the Afro-Latinx Lab at MSU. These images are based on the songs of Afro-Puerto Rican musician Ismael Rivera. While this series remains largely incomplete, these images capture fragments of time—like Rivera’s lyrics themselves—that offer a symbology of a people (Puerto Ricans) whose identities are found in constant flux.

The exhibit opens 2/18/22 at the RCAH LookOut! Gallery and is being digitized by AbleEyes and will be available online IN MARCH here.

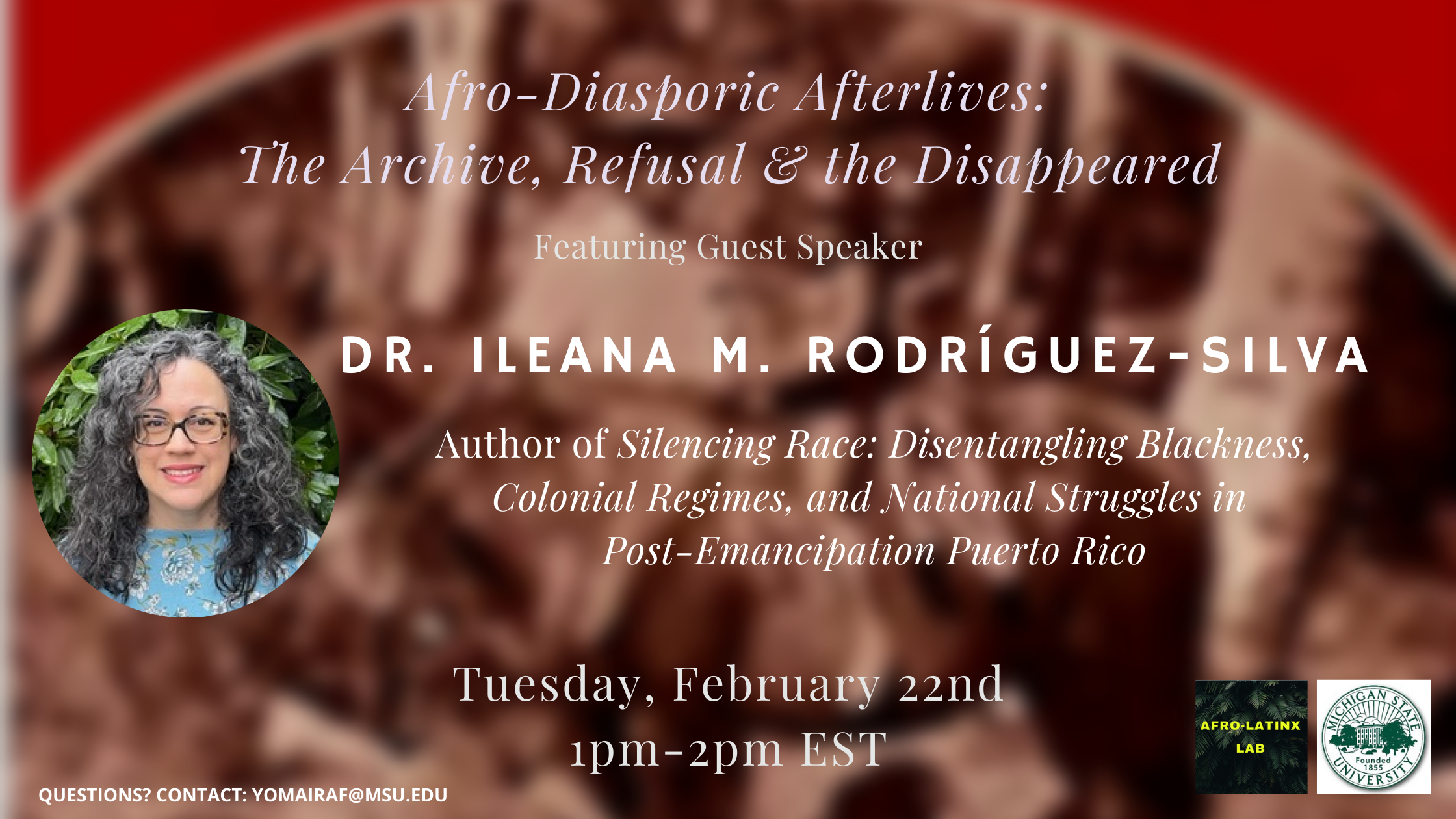

“Archival Silences in Puerto Rican Studies”

Ileana M. Rodríguez-Silva is associate professor of Latin American and Caribbean history and Director of Undergraduate Studies in the History Department at the University of Washington-Seattle. She is the author of Silencing Race: Disentangling Blackness, Colonial Regimes, and National Struggles in Post-Emancipation Puerto Rico (Palgrave, 2012).

In this clip from the Afro-Latinx Lab “Afro-Diasporic Afterlives” Speaker Series, she discusses her approach to researching, writing, and publishing Silencing Race and answers questions about the politics and archival practices of studying race and Blackness in Puerto Rico.

READ MORE: “The Caribbean House of Mirrors: Constructing Regions in Area Studies”

AFRO-LATINX LAB LECTURE SERIES

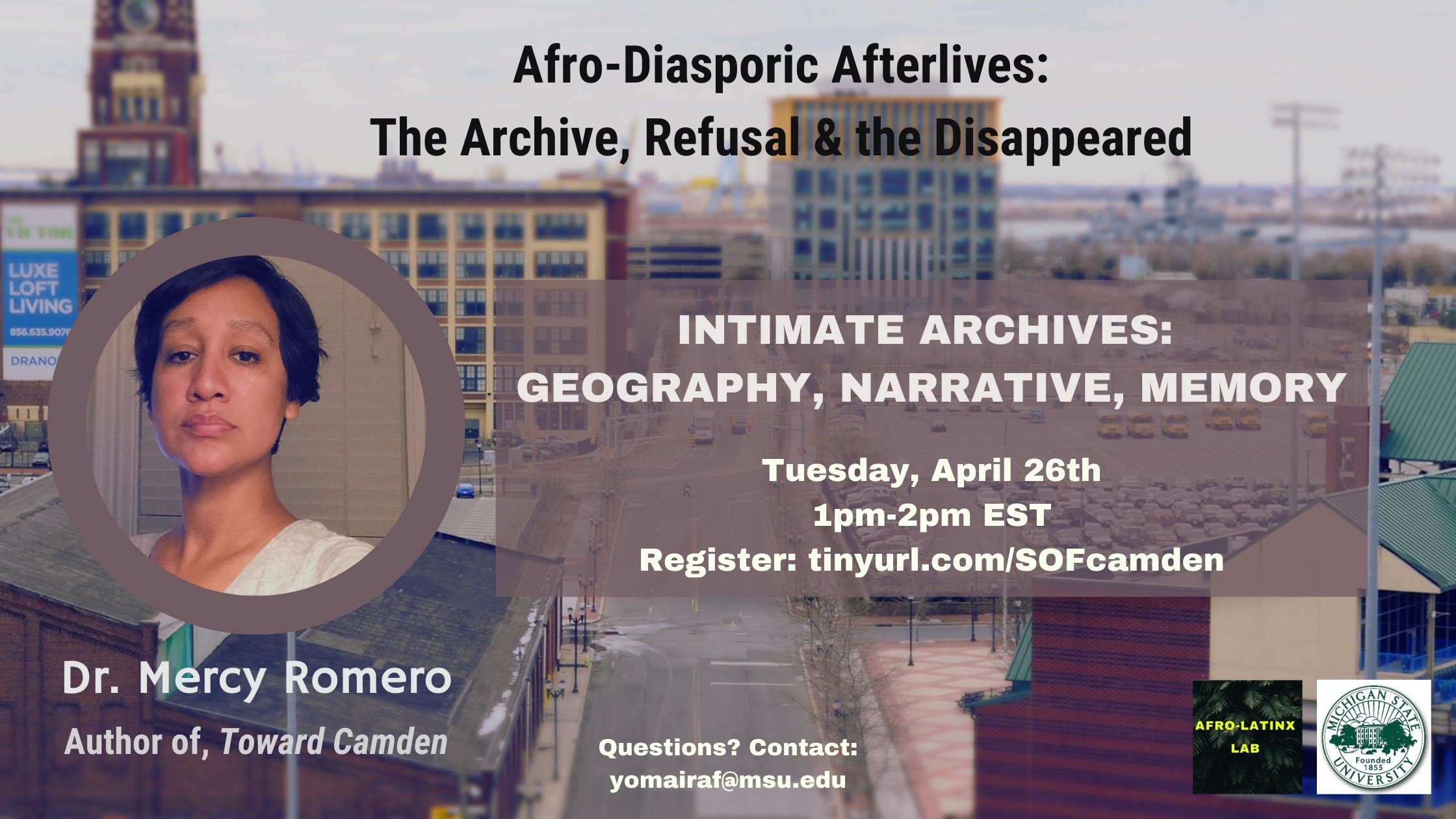

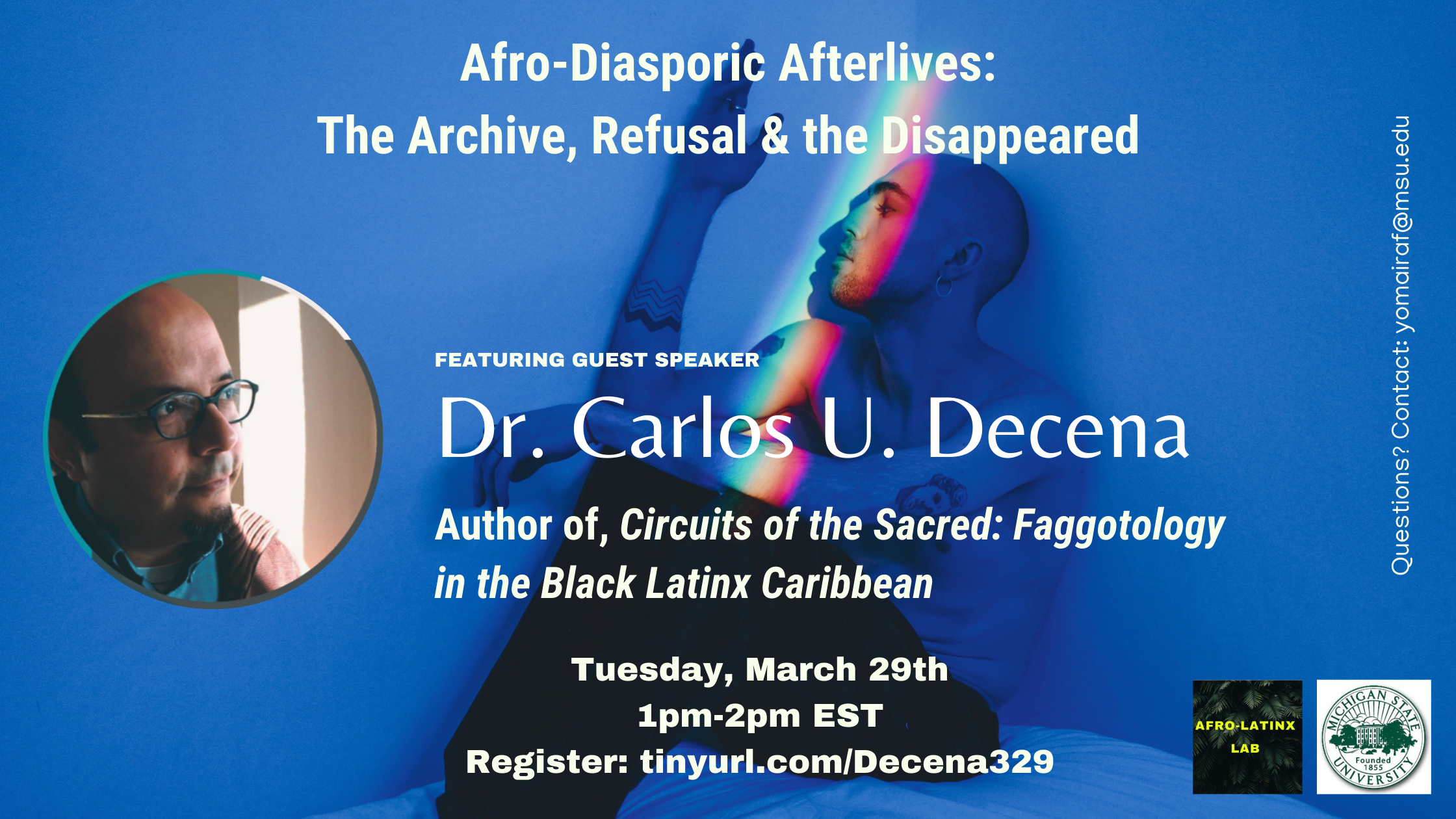

“Afro-Diasporic Afterlives: The Archive, Refusal & the Disappeared”A Cornell Society for the Humanities Seminar

A collaboration between the Afro-Latinx Lab at Michigan State University and the Society for the Humanities at Cornell University, this speaker series rooted in the themes and readings of the Spring 2022 seminar “Afro-Diasporic Afterlives: The Archive, Refusal & the Disappeared”.

Speaker Series Schedule:

2/22 Ileana Rodriguez-Silva “Archival Silences”

3/10 Carlos Decena “Archives of the Sacred”

4/19 Sebastian Pêrez + Chris López “Photography as Method”

4/26 Mercy Romero “Intimate Archives”

5/3 Mayra Santos Febres “Fiction as Archive”

“The Sacred as Archive”

Carlos Ulises Decena is an interdisciplinary scholar and writer. A member of the Rutgers University faculty since 2005, Decena teaches in the Department of Latino and Caribbean Studies and Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. He published his first book, Tacit Subjects: Belonging and Same-Sex Desire among Dominican Immigrant Men (Duke 2011). Circuits of the Sacred: Faggotology in the Black Latinx Caribbean will be published in Spring 2023 by Duke University Press.

“Photography as Archival Method”

Sebastian Perez & Chris Lopez

Sebastián Pérez teaches courses on race and ethnicity in American literature, Latinx cultural production, Caribbean diasporic aesthetics, & Cultural Studies theory. Dr. Pérez earned his Ph.D. in American Studies from Yale University where he also completed his B.A. in American Studies and Ethnicity, Race, and Migration. Prior to arriving at Fairfield, he taught and completed his dissertation research as a Bolin Fellow in Latina/o Studies at Williams College.

Christopher López (b.1984), a Puerto Rican-American photographer, was born in The Bronx and was raised between New York and Northern New Jersey. He began his career as an independent photographer in 2005 starting at the New York City based paper, El Diario La Prensa. Often by exploring diminishing histories, his photographs celebrate the richness of culture as well as portray the complexities of identity both on and off the island. His work was most notably featured in the exhibition, “Caribbean; Crossroads of the World” which spanned three museums in New York City and showcased over 100 years of Caribbean art from the region's most prominent artists. His works are currently in the permanent collections of El Museo Del Barrio, The World Trade Center Memorial Museum, and The Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. His most recent work, “The Afterlives of Ismael Rivera: A Visual Guide to the Heart,” explores the interpretation of songs through documentary photo practice.

“Intimate Archives, Memory & Geography”

Mercy Romero received her B.A from Barnard College (English) and her Ph.D. from UC Berkeley (Ethnic Studies). She teaches American literature and American studies in the Hutchins School of Liberal Studies at Sonoma State University. In her writing and research, she is interested in place making practices, structural abandonment, and the visual life of poverty, and how poetry and public art mediate a conversation about the “nowhere” sites of social suffering. Her first book, Toward Camden (Duke University Press 2021), thinks about Puerto Rican memory, demolition, and the built environment in post 1970’s Camden, New Jersey (her hometown). She has also written essays on Black/Latinx social movement archives. She is a former UC President’s Postdoctoral fellow. Presently, she is a National Endowment for the Humanities/Ford Foundation Scholar in Residence at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and a Flamboyan Foundation Arts Fund/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Letras Boricuas fellow.

“Fiction as Archive: Our Lady of the Night”

Mayra Santos-Febres was born in Carolina, Puerto Rico in 1966. She studied literature at the University of Puerto Rico and holds a Ph. D. at Cornell University. She has been a visiting scholar at Rutgers (1992), Cornell (1994) and Harvard University (2004), as well as Complutense University in Spain (2013), Autonomous University of México, at Yucatán campus (2008) and Leipzig University in Holland (2005). She co-created the Creative Writing Program for the University of Puerto Rico, and founded and directed The Word/ Festival de la Palabra, the most internationally recognized Literary Festival in Puerto Rico (2010-2009). Content Coordinator of Interdisciplinary and Multicultural Institute at the UPR, Mayra Santos–Febres is currently the Principal Investigator for the development of University of Puerto Rico’s Afro Diasporic and Race Studies Program, which has been recently awarded with a Mellon Foundation grant for academic diversification.

AFRO-LATINX LAB | SPRING 2021

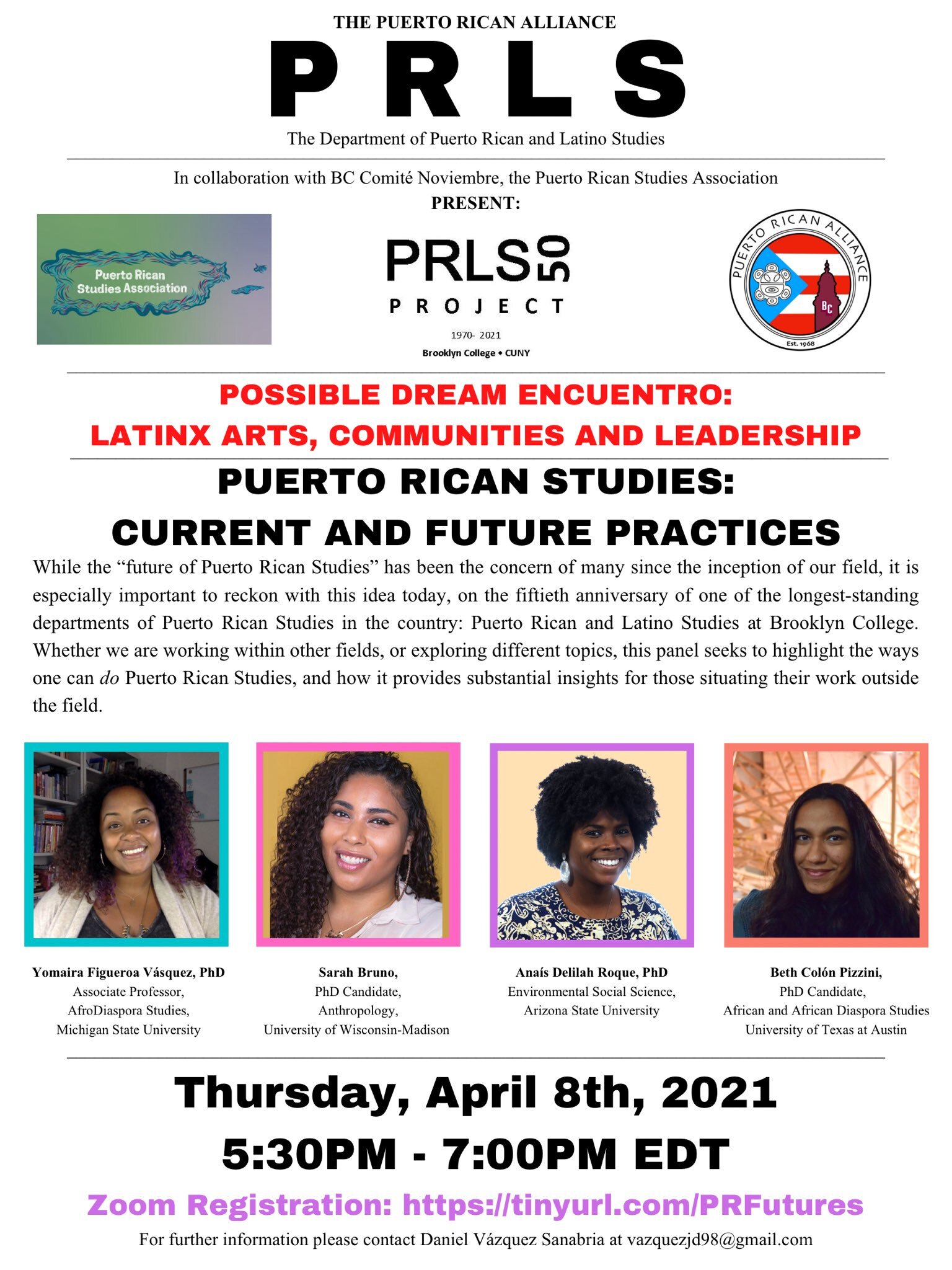

CURRENT & FUTURE PRACTICES IN PUERTO RICAN STUDIES

In the wake of hurricanes, earthquakes, political upheaval, the pandemic, ongoing femicides, anti-Black racism, and destabilizing austerity measures, what can Puerto Rican Studies tell us about Boricua past and futures? On Thursday April 8th, 2021 the Brooklyn College Department of Puerto Rican & Latino Studies’ Puerto Rican Alliance, in collaboration with the BC Comité Noviembre and the Puerto Rican Studies Association hosted an event to celebrate the 50-year anniversary of the establishment of Puerto Rican Studies at Brooklyn College. The panel comprised of a multi-disciplinary Afro-Puerto Rican feminist scholars signaled a radical shift in the field. This organizational movida not only centered racialized gender and Blackness as a central aspect of the future and creation of Puerto Rican Studies, but also was suggestive of the multiple and transdisciplinary approaches that reflect the environmental, embodied, archival, and sociopolitical preoccupations that will frame Puerto Rican studies in the decades to come.

In an effort to document these moment of encuentro and confluence of ideas, the Afro-Latinx Lab will highlight some of the reflections from the panel of scholars, activists, and organizers featured at the event.

Daniel Vázquez Sanabria

Brooklyn College ‘21, Event Organizer and Moderator

FRAMING PR STUDIES AT 50

The celebration of the fifty years of Brooklyn College’s Department of Puerto Rican and Latino Studies is one of joy—even with such uncertainty on the horizons. While the last fifty years can be encapsulated within a long history of struggle (for the departmentalization of both PRLS and Africana Studies at Brooklyn College, and the resources necessary to make us a community-oriented space in the ways we once were) we are here to say pa’lante. Celebrating this anniversary is about what lies beyond the neo-liberal campaigns that the ivory tower holds against our ways of thinking, and knowing. Thus, we root ourselves in radical teaching and building comunidad. This jubilee was about that which has been created, as a product of the initial fights for Puerto Rican Studies in the late 1960s, and what has persisted and evolved into much more than we could have ever imagined, una comunidad que no cesa de crecer.

Thinking of the coalitions that shaped our field fifty-years ago, Puerto Rican Studies: Current and Future Practices aimed to bring together scholars working within the field of Puerto Rican Studies while also holding Black and Africana Studies at homologous levels. The importance of both fields of inquiry, even half a century after their institutionalization in the country’s largest public urban university system, is such that the celebration would have been incomplete without the other. In addition, highlighting the amazing work of the Black Bori Women within the (very catchy) Rican Studies Renaissance was the core of this panel.

Through the format of a responsive panel discussion, the main goal of this event was to address long-standing questions about the ways that Puerto Rican Studies is and can be imagined. In short, we were interested responses that look towards the field as a site for critical productions of knowledge and as a locus for thinking about sovereignty and self-determination for the archipelago we call home. This event created space for an exchange between panelists, community members, and organizations that often find it difficult to work alongside each other. At the end of the day, we will be the ones who keep each other floating—colectivamente empáticxs sobre nuestras realidades.

Anais Delilah Roque Antonetty, Ph.D.

Postdoctoral Scholar of Environmental Social Science, Arizona State University

ON Environmental Social Sciences AND Post-Disaster Responses in Puerto Rico

I am trained as an interdisciplinary environmental social scientist. As a scholar, I work on the areas of disaster response and recovery, water insecurity, community resilience, social capital, environmental governance, and environmental (in)justice My most recent work focuses on post-disaster responses following the events of hurricane Irma and María. During this humanitarian crisis, I observed the lack of local and state preparedness for the hurricane season and how residents worked with the little that they had to support their neighbors, families, and the community more broadly. This experience ignited my passion to study how human societies can plan for, and respond to, complex disaster.

I’ve always considered Puerto Rican studies as a field that often focuses on migration and the Puerto Rican experience in the United States. Thinking about my field of study and experience, I believe there is much work to do in the area of Afro-Boricua experiences, health disparities, climate justice, government induced migrations, and environmental justice. These topics can be addressed individually and collectively (e.g. Afro-Boricua health experiences and environmental justice). Puerto Rican Studies is a responsive field; one that addresses challenges that our communities face due to structural inequalities in the United States and in Puerto Rico. In terms of environmental studies, I am attentive to how environmental issues compound challenges in the archipelago and our diasporic communities. For example, the coal ash deposits that were being dumped in Puerto Rico are now being disposed of in Florida, which has one of the largest PR communities in the United States.

Puerto Rican experiences can inform fields in environmental studies, sociology, political science, and engineering to mention a few. Unfortunately, the mismanagement of Puerto Rico offers us a lens to explore a variety of issues that range from infrastructure to family, health, race, ecology, and drought. Puerto Rico is an ideal point of departure to engage in different fields of inquiry and scholarship and to advance knowledge production to action research. We need to consider how we can use our academic knowledge to support transformation towards equity and justice. This way, the causes of Puerto Rican Studies must find its way into schools, decision making spaces, and the informal familial space of the kitchen table.

I look forward to seeing more ethical and collaborative work amongst people in Puerto Rico and the diaspora. In the wake of Hurricane María for example, I saw many researchers “parashoot” to the archipelago and while their research is important, it is important to for those in the diaspora to support researchers on the ground. More of these kinds of collaborations would have been valuable and would have amplified the experience of Puerto Rican scholars amid the austerity measures. By developing joint efforts, academics in the diaspora can leveraging resources (e.g., funding, students, library sources, etc.) to advance Puerto Rican studies research from within the archipelago.

Puerto Rican Studies must engage more critically and intensively with issues of environmental injustices and race in Puerto Rico and Puerto Rican communities in the U.S. as well as issues of health disparities, water, energy, and food insecurity. Centering the environment in the Anthropocene will be important to reduce climate migrants and inequalities in access to human rights. I also hope to see more research that presents Puerto Rican experiences in positive perspectives. As researchers, we are trained to focus on the problems or “gaps” in knowledge, but there are ways to also elevate the positive efforts, experiences, and outcomes. For example, in my own research I examine community resilience (a term that has been critiqued with the best of intentions) in Puerto Rico after Hurricane María. Acknowledging the work of these communities and learning from their experiences, is one way to show that another Puerto Rico is possible.

Beth Colón-Pizzini, PhD,

Department of African and African Diaspora Studies, University of Texas at Austin

ON BLACK PUERTO RICAN IDENTITIES, POLITICS, AND ART

When it comes to my scholarly interests within the field of Puerto Rican Studies, I focus on Afro-Puerto Rican politics, history, and culture. I come from a Black Studies Department that recognizes that Diaspora and Blackness travel, transform, and are never-ending. This has allowed for me to appreciate just how Black identities and cultures from other Caribbean countries have had a great influence on Black Puerto Rican identity and culture and vice versa. The same is true in the context of Black U.S. identities and cultures. Whether we’re presenting qualitative or quantitative scholarship about Puerto Ricans, in the archipelago or the Diaspora, Blackness (and racial formations) should always be central in Puerto Rican Studies. That’s the hill I’m dying on as an academic in this field.

Blackness is at the center of my Puerto Rican and Caribbean Studies. I bring in the critical issues of gender, sexuality, economic extraction and state violence, and the larger structures of colonialism which I examine through close readings of various cultural moments, artifacts, and trends. For example, in my dissertation, Libres, Peligrosas, y Todopoderosas: Afro-Puerto Rican Women’s Feminist Decolonial Art through El Verano del ’19 (2021), I delve deep into Artistas Solidarixs y en Resistencia’s La Puerta and Moriviví’s Paz para la Mujer murals; examine feminist folklore acts Ausuba and Plena Combativa; and contextualize the perreo combativo event within the larger classed, racialized, and gendered history of reggaetón, to discuss the diverse ways Afro-Puerto Rican women artists create work that aligns with decolonial Black feminist activism and politics in the archipelago that we saw come to a head in the summer of 2019. I am intentionally carving out a space in the academy for contemporary Afro-Puerto Rican women artists that are building and affirming their racialized, gendered, and classed subjectivities while building a politic that is outside the norm of colonialism, whiteness, heteropatriarchy, and capitalism.

The intricacy of this politically significant work from Afro-Puerto Rican artists is why I never want to study Puerto Rico or write about Puerto Rico in a way that makes it seem like it exists in a vacuum, because it does not. Puerto Rico is global. It’s part of an empire, but it’s also part of a larger Diaspora of Black people. That complexity and simultaneity is important to my work and, increasingly so, to the field of Puerto Rican Studies, which is exciting to see and I’m glad I get to participate in that. Moreover, because of the intricate interconnection of issues within Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricanness, the future of the field merits a lot more collaboration between academics. We can connect environmental sciences with culture, for example, when it comes to the study of Puerto Rico. Additionally, queer sexualities and non-normative genders should not be a sprinkling on our programs and publications; working class perspectives should not be shut out of the field; and neurodiversity and disability should be part of our work too.

Sarah Bruno, Ph.D.

Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

On Bomba and Black Intellectual Genealogies

My project stemmed from wanting to see where Black Boricuas were placed in Puerto Rican history. When I took a Puerto Rican history class as an undergrad at UW-Madison there was little said about Afro-Puerto Ricans after emancipation. That really stuck with me because I always wondered how that erasure happened. It sowed a deep curiosity within me and when it came time for my doctoral research, I centered my project within a Black diaspora studies framework.

In my fieldwork I paid attention to how the Afro-Puerto Rican genre of bomba can be used to map out a historical cartography of Black Puerto Rican affect and embodied practices. Bomba is regarded as the oldest genre of Puerto Rican music and as such it becomes the optimal space for the investigation and plotting of Puerto Rican endurance. In fact, José Luis González names the Black enslaved folks who were the original creators and participants of bomba as the first Puerto Ricans. I wish that this conceptualization of Puerto Ricanness was emphasized to me when I was first exposed to José Luis González, because it repostures Puerto Rican Studies within a Black intellectual genealogy. And that is what I and a lot of more recent scholars are aiming to do: rethinking Puerto Rican history within the context of Afro-Puerto Rican life and practices.

Puerto Rican studies has a great investment in expressive cultures and by doing our field already centers lived experiences. Within my own discipline I feel that I am constantly defending Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans in general. Anthropology has harmed Puerto Ricans in numerous ways, here I am thinking about the ways Oscar Lewis portrayed Afro-Puerto Ricans in La Vida (1966) and then diagnosed us as having a “culture of poverty”. So many anthropologists with no ties to Puerto Rico or its diaspora continue to diagnose their field sites similarly, but within Puerto Rican Studies many of the scholars already feel a responsibility to participate in ethical research and produce ethical scholarship. I would like to see more studies of Black Puerto Rican life and affect and emotion. Puerto Rican studies is a generative space for considering how emotion and affect comes into play — but I admit that I am biased because that is the work I am doing with bomba.

I would hope that people outside and inside of Puerto Rican Studies would notice not only projects being done on art, music, dance, etc., but also how Puerto Rico and its relationship to the United States can be used as a case study for colonialism. Puerto Rico is a model for the ways empire entangles colonies so deeply within its nest that people aren’t even aware of the limits of colonialism. I wonder how we can discuss sovereignty and decolonization if we aren’t fully aware of how entangled Puerto Rico is with the United States. That’s the trick of white supremacy, its keeps people in obscurity as to the extents of its domination so that its limits or lack thereof are secrets.

I use Dr. Figueroa-Vásquez’ analytic of destierro as a framework to animate the work that I see bomba doing for Puerto Ricans in the diaspora and in Puerto Rico. Destierro is this deep untranslatable uprootedness, a being torn away from a homeland. I am thinking particularly about the disastrous wake of Hurricane María, the displacement after the earthquakes in 2019 and 2020, and about Boricuas born in the diaspora who may an embodied loss. Within this context of destabilization and dispossession Bomba becomes a place of healing. The batey, in particular, becomes a place that operates outside of pinned geographical space and linear time that allows bomberxs to attend to, or use bomba as a balm to mitigate this loss. The batey is built on care and intimacy and it has endured throughout history as a Black Puerto Rican epistemology. Thus, the batey becomes is a space where historically displaced Black peoples, whether previously enslaved in the archipelago or Afro-Caribbean migrants from neighboring islands, are welcomed and recenter themselves through the bomba community. I believe bomba accounts for the ways Afro-Puerto Ricans mitigate the intimate losses accounted for under destierro, as well as the infrastructural losses. Not only are individuals able to cope and participate in a communal practice of togetherness to combat this deep feeling of exile, but the batey expands as bomberxs are all across the empire and become a network of mutual relief to send resources to those in need in Puerto Rico during moments of catastrophe to act as a salve to the imperial neglect under which Puerto Rico exists.

Yomaira C. Figueroa-Vásquez, Ph.D.

Associate Professor, Department of English, Michigan State University

on Method, Struggle, Language, and SOVEREIGNTY

My entry into academic Puerto Rican studies began as an undergraduate at Rutgers. I was first was resistant to, and later excited by, the unearthed histories that I encountered in the courses. My first book project examined Afro-Puerto Rican, Afro-Dominican, Afro-Cuban, Equatoguinean cultural productions in relation. What initially began as a study of late 20th c. Puerto Rican literature became a hemispheric and transnational project that examined the experiences of African and Afro-diasporic subjects and how their literary works bear witness to our lives in this world while also fomenting practices that move beyond logics of enclosure and colonialism. In my next book, I am pivoting from a global Black project to a Puerto Rican Studies project that examines how Black Puerto Ricans and Black Puerto Rican life are erased from the archive, statistical data, demography, and other records, while also looking at alternative archives including films, photography, and narratives produced on the islands and diaspora that document the survival of Afro-Boricuas beyond the erasure produced by the colony and empire. Suturing the archival material that we do have with familial stories, letters, and ephemera, I hope to add to the rich work that exists in Puerto Rican Studies while also challenging the canonical conservative works that lean on discourses of mestizaje and racial democracy that erases, silences, and obscures the racialization and racial/gendered violence of ongoing colonialism.

As humanistic Ethnic Studies scholar, studying Puerto Rico and its diaspora offers so much to modern thought – from philosophies of being to sovereignty and ecology to environmental justice. Oftentimes it is forgotten that Puerto Rico is the modern world’s oldest colony. Examining the Puerto Rican archipelago and our diaspora also complicates many established methods and normative understandings of phenomena and leads and requires new methods beyond conventional approaches. Puerto Rican Studies also enriches and transforms fields such as digital humanities—as seen by Taller Electric Marronage—which comes from the thinking of two Afro-Puerto Rican scholars and enriches History, Literature, English, Ethnic Studies. Much of my work is grounded in the facets of the Comparative Ethnic Studies ethos I learned in graduate school and my undergraduate work in Literature, Puerto Rican Studies, and Women’s and Gender Studies.

A Comparative Ethnic Studies approach can help us challenge narratives “insularity” in Caribbean, Pacific, and other locales. Simply put, it helps us to imagine the world differently. Archipelagic studies can help us to stop looking at Puerto Rico from the mainland and to put our feet on our islands — to look at the diaspora as extension of the Caribbean and the Caribbean as a set of archipelagos among many other archipelagos. Insurgent work is necessary and vital to creating heretical practices -that do not allow for reversion to traditional, disciplinary, imperial thinking- as we take up causes of Puerto Rico and its anti-colonial and decolonial futures.

Puerto Rican Studies is on shifting ground and is in an optimal moment to rethink what we take up as “canon” in our field. Placing Puerto Rico within relational, hemispheric, and global perspectives complicates established notions of “H”istory that have not been helpful for Black Puerto Ricans and others erased from the record. Discrete studies of Puerto Rico can often misplace and erase overlapping dispossession and disaster, overlapping music and cultural production, overlapping feeling and emotion for the Caribbean and beyond. Discrete studies of Puerto Rico will often replicate bourgeois class, racial, and gender politics that make claims about what kinds of culture Puerto Rico does and does not have, construct who is of the nation through temporal and spatial moves (who is in the present, who is of the past, and who is folkloric), and create foundational histories that claim to represent but instead misrepresent the majority of Puerto Ricans especially workers, queer folks, and Black people. These people are not represented by the creole and bourgeois histories that are shoved down our throats both in Puerto Rico and in the diaspora. This is as an exciting time to fuck-up the disciplines, to shift and rethink established work, to read against the grain or not engage at all with the racist, sexist, exclusionary texts. We have and will continue to document and create our own histories by listening to our families, kin, and being faithful witnesses to the quotidian and the extraordinary. It is imperative that we stop taking Eurocentric theories and approaches as the framework to make legible the study, people, lives, and struggles of Puerto Ricans. We use our experiences as a guide to show how we push and create new modes of thinking, being, and relating in the world. This is possible. It is already happening.

Within the academic strata, somos pocos. Puerto Rican Studies researchers often do our work in isolation of one another due to disciplinary or field specific methods. We must continue to connect ourselves and our university resources (if we have them) to working-class and grassroots organization and support autogestion and self-determination projects (and to align ourselves with our colleagues in the UPR system who contend with extreme austerity measures and institutional/state neglect). We must follow in the radical footsteps of our past, change what does not work, at the intellectual, structural, political level. Recently, the reencuentro of Kanaka/Boricuas (Hawaii/Puerto Rico) Twitter made me reflect on the longer histories of radical relationality; particularly the work of photographer and activist Frank Espada in his Chamorro Documentary Project, documenting our kin in Guåhan (Guam). We are not alone in our imperial colonial subjectship. The work of relating across differences is way to map another way forward.

Language as such an essential part of this. Tenemos que bregar con la cuestión del lenguaje - especialmente en el caribe y la diáspora. O sea, podemos imaginarnos proyectos en el cual nos emparejamos investigadores haciendo trabajo en español o inglés, ayudarnos uno al otro. Hemos visto que muchos de los discursos en el cual dicen que el caribe está fracturado por imperios y por lenguajes – pero vemos también el trabajo de personas como Yolanda Martinez-San Miguel y otres que estudian las migraciones entre Puerto Rico y el caribe. Translation can make our research more accessible and render it more visible in multiple communities. We need to get creative in how we are going to communicate and collaborate across language. Translation is not just an ethics and communications question, but also of money, time, and audience. However, we need to hold firm in the fact that no matter how difficult the process may be, we are not just engaging in intellectual projects but rather a political project with sovereignty at its horizons.

Puerto Rico has been a colony since before the nation-state came into existence in modernity. Because of that Puerto Rico can be a locus for thinking beyond the nation-state and for reimagining sovereignty. I am a firm believer that full sovereignty for Puerto Rico would not work without a enormous reparations package. How can this happen if Puerto Rico is not part of the CARICOM efforts for reparations? What does this look like beyond statehood or independence that would create conditions that would put us under the confines of a neocolonial order such as the IMF bank? How can we think about this outside of the categories that we have inherited through modernity? How can a nation of islands that have existed before the creation of the nation state help us to think about our futurities? These are just some of the questions we must continue to contend with in our work and actions. We are in the midst of a multi-faceted struggle: fighting the structures that are extinguishing our lives and limiting our prospects, and then working toward our sovereign futures. It is not one or the other, it is both simultaneously.

SPRING 2021 AFRO-LATINX LAB LECTURES

[listen-in on our Spring 2021 Black Studies class via the audio lectures & readings]

Bárbara Abadía-Rexach, Ph.D.

“Saluting the Drum! The New Puerto Rican Bomba Movement”

Dr. Bárbara Abadía-Rexach is an Assistant Professor of AfroLatinidades at San Francisco State University.

In this clip from the EM Afro-Latinx Lab she discusses Afro-Latinxs, Afro-Puerto Ricans,Racialization, Blackness, Identity Formation, Bomba as Popular Culture, Music & Race in Puerto Rico, and Black Hispanic Caribbean & African Diaspora.

SFSU Interview: “Professor reflects on Latinx and Hispanic Heritage Month”

Black Latinas Know Collective [BLKC]: “Afrosanando heridas”

CITATION/ARTICLES IN PDF: “Mujeres puertorriqueñas: alertas y combativas = Puerto Rican Womyn: Alert and Combative”

Pablo Lopez Oro, Ph.D.

“Indigenous Blackness in the Américas: The Queer Politics of Self Making Garifuna New York”

Dr. Pablo Lopez Oro is Assistant Professor of Africana Studies at Smith College.

In this clip from the EM Afro-Latinx Lab he discusses the politics of self-making within diasporic Garifuna Communities with a group of Black Studies undergraduate students at Michigan State University.

Omaris Z. Zamora, Ph.D.

“BLACK LATINA GIRLHOOD POETICS OF THE BODY”

Dr. Omaris Z. Zamora is an Assistant Professor of transnational Black Dominican Studies at Rutgers University.

In this clip from the EM Afro-Latinx Lab she performs some of her spoken-word poetry and discusses AfroLatinidad in the context of race, gender, sexuality through Afro-diasporic and feminist embodied approaches.

READ MORE: “Black Latina Girlhood Poetics of the Body: Church, Sexuality and Dispossession”